The Wi-Fi Test That Passes in the Lab and Fails in the Real World

- Dan LANCaster

- Jan 18

- 6 min read

If you have ever validated a Wi-Fi upgrade in a quiet lab and then spent the next week explaining to users why “everything looks fine on our end,” you already know how this story ends. The lab test measured the PHY at its best. The real network lives and dies by airtime.

This post is for Wi-Fi engineers. It is not about chasing the largest number once. It is about understanding why that number collapses at 10:30 AM on a Tuesday, and how to test in a way that predicts what users will actually experience.

The Clean-Lab Fallacy

A classic validation setup looks like this:

One AP, one client

A fixed channel in a quiet part of the band

Short distance, stable orientation

No neighboring BSSs, no background traffic

In that environment, you are not really testing a network. You are measuring the ceiling of a single link. That is useful. It tells you the radio works. It does not tell you how the network behaves when airtime is shared, clients roam, uplink traffic appears, and someone sits in the hallway with a marginal signal.

With Wi-Fi 7 (802.11be), this trap is easier than ever to fall into because the ceiling looks spectacular!

What “1.4 Gbps PHY” Actually Means in Practice

Imagine a very common lab scenario: Wi-Fi 7, 80 MHz channel, 2x2 client, 4096-QAM (MCS 13), short GI, clean RF, no retries. In this setup, the client may advertise a PHY rate of up to 1.4 Gbps. That number shows up in the status screen and immediately makes everyone feel good. But here is the part that matters:

On real hardware, that PHY rate typically translates into 700–850 Mbps of sustained TCP downlink throughput in a clean, single-client lab test. Short bursts may peak higher, but this range is a realistic ceiling. That is already an great result. It is also the absolute best case: one client temporarily monopolizing the medium. The mistake is assuming this number has anything to do with capacity once airtime is shared.

Let’s imagine something even better: 160 MHz channels. At 160 MHz, the illusion gets stronger. A 2x2 Wi-Fi 7 client at MCS 13 may advertise a PHY rate around 2.9 Gbps. In a short demo, this looks incredible; you can achieve a sustained TCP throughput of up to 1.4 - 1.6 Gbps. But even in a lab, efficiency drops compared to 80 MHz due to:

Higher thermal noise (+3 dB)

More fragile SIR requirements for 4096-QAM

Less stable aggregation over time

Now add a dense office or school environment and things get worse quickly. Which brings us to the part many demos quietly skip.

Why Wide Channels Are Usually the Wrong Choice in Dense Enterprise

In offices and schools, channels wider than 40 MHz should generally not be the default, and this is not a matter of opinion. It is physics and geometry.

Not enough channels

Wider channels reduce reuse. More APs end up sharing the same channel.

Higher SIR requirements

High-order modulation survives only in very clean RF. Interference, not RSSI, becomes the limiting factor.

Higher thermal noise

Doubling bandwidth raises the noise floor. SNR drops, MCS drops, airtime cost per bit rises.

Wide channels produce beautiful screenshots and fragile deployments. Narrower channels produce boring graphs and stable networks. But hey, in enterprise Wi-Fi, boring is good :-)

Why Single-Client Throughput Lies by Omission

While Ethernet shares bandwidth, Wi-Fi shares airtime.

Airtime is the scarce resource, and everything else is just downstream of that fact. In real offices and schools, you have many clients with different RF quality, constant management and control traffic, co-channel neighbors (often your own APs), and at least one client that insists on talking very slowly. A single-client test answers exactly one question: “Can this client efficiently consume most of the airtime when nobody else is talking?” It does not answer how airtime is shared, how uplink behaves, how retries scale, or how latency behaves under load, which is why networks that “passed validation” so often feel unpredictable during peak hours.

Co-Channel Interference: Polite, Destructive, Invisible

Co-channel interference is not primarily about collisions; modern Wi-Fi is polite, devices defer, they take turns. However, that politeness is the problem. When multiple BSSs share a channel, airtime is divided, scheduling becomes uneven, and inefficient transmitters consume more than their fair share. This is why adding APs can reduce performance if channel planning is sloppy: coverage improves, capacity does not. A clean lab with one AP hides this entirely!

Hidden Nodes and Directional Blindness

Hidden nodes are still responsible for an impressive percentage of “mysterious” Wi-Fi failures. The pattern is familiar:

Client A hears the AP and Client B hears the AP

A and B do not hear each other

Uplink frames collide at the AP, triggering retries and backoff

Retries explode. Airtime disappears

Downlink-only tests often look fine because the AP’s RF behavior is better than most clients. Uplink and bidirectional tests expose the problem immediately. And yes, uplink matters, because one needs it for voice and video calls, screen sharing, cloud collaboration, etc. If uplink is unstable, the user experience is unstable, and no amount of downlink throughput can fix that.

RSSI is Not Throughput, and Never Was

Unfortunately, high RSSI alone does not guarantee high SNR, high SIR, low retries, or stable MCS. In labs, clients sit still. In offices and schools, devices move, rotate, cluster, and roam. Rate adaptation becomes dynamic, and airtime efficiency fluctuates.

In schools, Wi-Fi clients behave exactly like the kids carrying them: they form dense clusters for no obvious reason, disperse suddenly, roam constantly, ignore every assumption made during planning, and succeed in driving not only the APs but also the engineers and administrators to the brink of madness. If you are a parent, you know what I mean — sigh.

The common symptom is that short tests look fine, but sustained tests show rising jitter and latency. Users complain about “lag” while Mbps still looks respectable.

Airtime, Loss, and Client Count — One Ugly Picture

Below is a simplified but realistic shape for a Wi-Fi 7 cell in an office or classroom using 40 MHz channels and mixed clients. The important part is not the exact numbers. It is the shape: airtime saturation is the cliff, loss and latency rise non-linearly, users feel pain long before throughput hits zero.

Let me tell you a real failure story (anonymized). An organization upgraded an office and training facility to Wi-Fi 7. Validation used a single modern laptop near the AP on a wide channel. PHY rates were huge and short TCP tests were impressive, so everyone signed off. Of course.

First week of real usage:

Video calls stuttered mid-morning.

Training rooms froze during screen sharing.

Signal strength looked perfect.

The real causes were boring and predictable:

Wide channels reduced usable capacity through reuse.

Hidden nodes broke uplink under load.

One weak client consumed a disproportionate amount of airtime.

Fixes were equally boring:

Standardize on 40 MHz in dense areas.

Clean up the channel plan.

Validate with multi-client, bidirectional, sustained tests.

While peak demo numbers went down, user experience improved dramatically. No magic. Just honesty.

What a Real Acceptance Test Looks Like

A useful acceptance test answers one question: Under realistic contention, do loss and latency stay below application-breaking thresholds? For offices and schools, by “realistic” I mean 8–20 active clients with mixed distances and capabilities, simultaneous downlink and uplink traffic, sustained duration (minutes). You can begin with baseline sanity (a single-client TCP downlink and uplink near the AP) and then move to stressful reality, which I talked about in one of the previous blog posts, i.e. multi-client load tests with gradual load ramp-up using Tessabyte. Check for UDP loss onset; use rate-limiting in Tessabyte to find the stability cliff.

No hero numbers. No surprises later.

Conclusion

Lab tests measure ceilings. Offices and schools live on margins. If you validate Wi-Fi 7 with wide channels, one close client, and downlink-only TCP, you will get beautiful numbers and fragile deployments. If you validate with realistic channel widths, shared airtime, bidirectional traffic, paced UDP, and sustained runs, your headline Mbps will be lower — and your network will actually work.

That is the difference between a demo and engineering. Oh, and I almost forgot one more tip and I'm pretty sure no one has told you about it...

A Single Click That Can Invalidate Your Test Data

You know that Wi-Fi network selection dialog that appears when you click the Wi-Fi icon in your favorite OS? The one that lists networks in the vicinity:

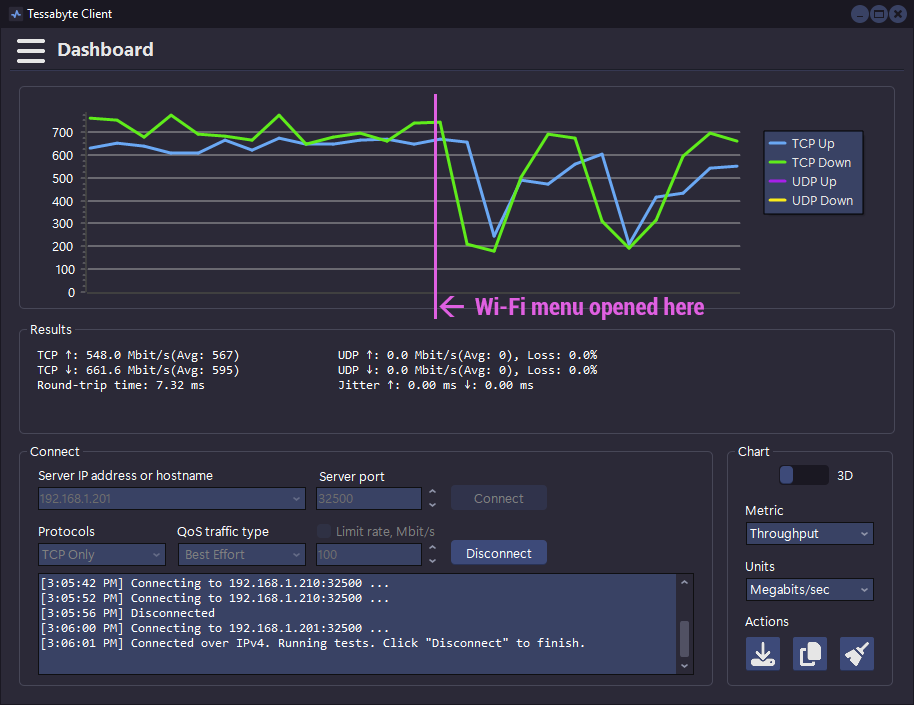

Well, I have some bad news. What do you think happens when this dialog pops up? Right. Your wireless adapter begins sweeping the ether, hopping from one channel to the next, then to the next band, trying to find all networks around you. The problem is that most client adapters have only one radio, and this radio can be tuned to only one channel at a time. Like with your TV, you cannot watch a movie and, at the same time, search for a better one that may or may not be broadcast on a different channel. So, the moment you click the Wi-Fi icon, bad shit usually happens to your Wi-Fi throughput:

See how throughput collapsed from a stable 700 Mbps down to 200 Mbps? That is scanning in progress. Do not click the Wi-Fi icon while conducting network tests and whatever you're using (Tessabyte, iperf, or smoke signals), don't trust results while the Wi-Fi menu is open.

Comments